1. Social Security is not going bankrupt

|

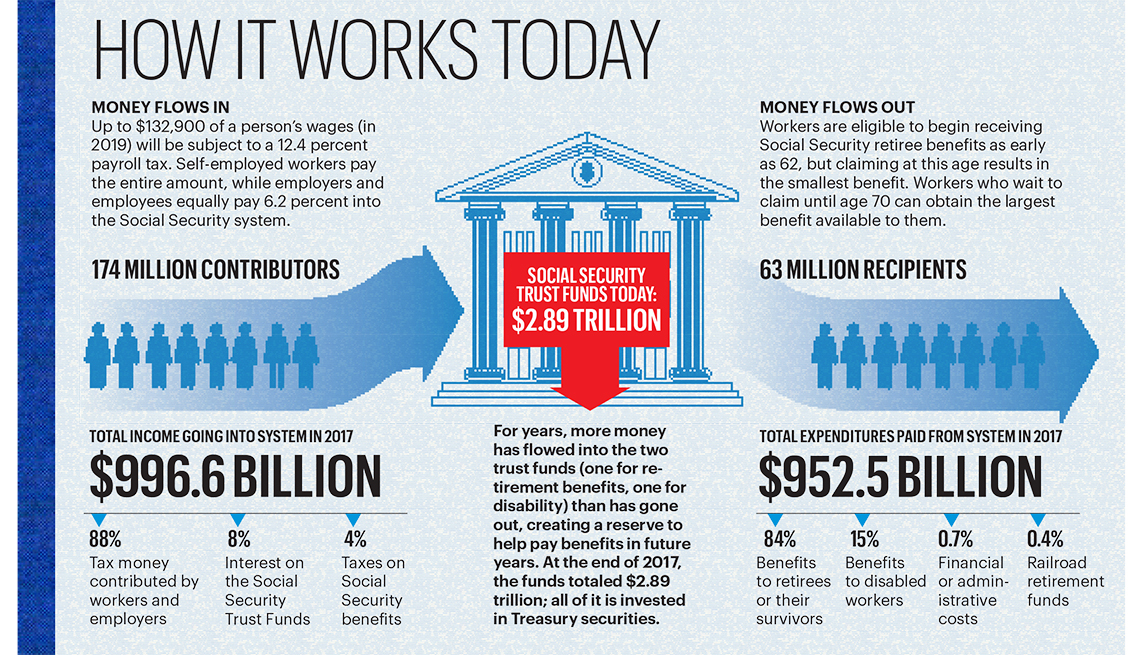

At the moment, you could say the opposite; the Social Security trust funds are near an all-time high. “The program really is in good shape right now,” says David Certner, AARP’s legislative policy director. “But we know it has a long-term financial challenge.” Here’s why: For decades, Social Security collected more money than it paid out in benefits. The surplus money collected from payroll taxes each year got invested in Treasury securities; today, the trust fund reserves are worth about $2.89 trillion. But as the birth rate has fallen and more boomers retire, the ratio of workers to Social Security recipients is changing. This year is a tipping point: The program will need to dip into its reserves to pay full benefits from this point forward, absent any change to the program. It’s now forecast that the trust fund reserves could be exhausted in 2034. Even if that happens, Social Security won’t be bankrupt. The program will continue to pay benefits, but at a rate of 79 percent of what recipients expected to receive. But if the goal is to keep benefits at their current levels, the sooner funding issues are addressed, the better. The reason is simple: The earlier you make needed adjustments, the less dramatic they need to be. “The longer we wait to fix Social Security funding, the more the cost will be paid by the younger generations, either on the tax side or the benefits side,” says Kathleen Romig, a Social Security analyst at the nonpartisan Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

2. Congress probably will not take up Social Security reform anytime soon

Several members of Congress have proposed legislation to address the program’s long-term funding issues. But given the deep political divides on Capitol Hill, it’s unlikely that Congress will make any effort to reform Social Security until there’s the possibility of bipartisan support. “Because Social Security is so important, we need to be really thoughtful and deliberate about how to make change,” Romig says. “And we want a bipartisan consensus because we want the change to last.” There are concerns that the tax-cut legislation passed in late 2017 could lead some lawmakers to look for places where they might cut spending. “The stage has been set by the tax bill to take another run at Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid,” says Max Richtman, CEO of the National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare. Control of Congress after this year’s elections will play a key role in how Social Security’s funding is addressed.

3. Some ideas to reform funding are starting to take shape

One proposal is to either raise or eliminate the wage cap on how much income is subject to the Social Security payroll tax. In 2019, that cap will be $132,900, which means that any amount a worker earns beyond that is not taxed. Remove that cap, and higher-income earners would contribute far more to the system. Other options lawmakers might consider include either raising the percentage rate of the payroll tax or raising the age for full retirement benefits.

4. Lawmakers do not raid the trust fund

Another common myth about Social Security is that Congress and the president use trust fund assets to pay for other federal expenses, such as education, defense or economic programs. That’s not accurate. The money remaining after the Social Security Administration (SSA) has paid benefits and other expenses is invested directly into U.S. Treasury securities. The government can use the money from those securities, but it has to pay the money back with interest. Congress does get to determine each year how much the SSA spends on administrative costs, which includes staffing at field offices and call centers. In the most recent fiscal year, the SSA got an increase of $480 million, which raised the agency’s administrative budget to more than $12 billion.

5. Many believe it can be run better

As you would expect, the SSA is a big operation, with more than 60,000 employees and 1,200 field offices nationwide. With the rapid increase in the number of retirees, the agency has struggled to keep up. “There aren’t enough resources to take care of all the people now, and another 10,000 people turn 65 every day,” Richtman says. A recent audit showed that average wait times at field offices increased 32 percent between fiscal years 2010 and 2017, for example. During that same period, the number of visitors who had to wait over an hour to be seen at a field office nearly doubled.

6. Your Social Security benefits can be taxed

If you have other income in addition to Social Security, you might have to pay federal taxes on your benefits. Single filers whose combined annual income exceeds $34,000 might pay income tax on up to 85 percent of their Social Security benefits; couples filing jointly may pay tax on up to 85 percent if their combined income tops $44,000. And 13 states tax Social Security benefits depending upon differing variables: Colorado, Connecticut, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Rhode Island, Utah, Vermont and West Virginia.

7. Social Security is not meant to be a retiree's sole source of income

The SSA says if you have average earnings, the program’s retirement benefits will replace only about 40 percent of your preretirement wages. Nevertheless, 26 percent of those 65 and over who receive a monthly Social Security benefit today live with families that depend on it for almost all of their retirement income. And 50 percent of them say their families depend on Social Security for at least half of their income.

8. The purchasing power of social security is diminishing

Every year, the SSA issues a cost-of-living adjustment (COLA), which is an annual adjustment that beneficiaries receive to help their monthly checks keep up with inflation. However, the formula used to calculate the COLA does not fully account for the medical costs of an average older American. These costs have been increasing faster than other goods and services. An average American 55 and older spends about 27 percent more annually on health care than the overall population, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

9. You can work and get Social Security

But beware The agency will withhold some of your benefit if you are younger than full retirement age and your earned wages exceed a certain limit. In 2019, the threshold on your earnings will be $17,640. Make more than that, and the government will temporarily withhold $1 from your benefit for every $2 earned over the cap. You will receive this money eventually, in the form of higher benefits once you hit your full retirement age. If you wait until full retirement age to start drawing Social Security, you can work as much as you like and your benefits won’t be reduced.

10. Social Security has gone digital

The U.S. Treasury Department has moved away from sending out paper checks in favor of electronic payments. The SSA also has set up an online portal called My Social Security, where you can track your benefits. People are encouraged to go to the website (ssa.gov/myaccount) and set up an account. It will help prevent scammers from setting up an account in your name and possibly stealing your benefits.

11. Social Security is not just a retirement program

There are four main types of Social Security benefits: retirement, disability, dependent and survivor. Sometimes a person can qualify for more than one of these. However, Social Security generally will only pay one benefit at a time to a person. When filing for benefits, you should make sure to ask about your eligibility for other benefits. And if there is a change in your family status, such as the death of the family breadwinner, you should inform SSA of his or her death and ask if you or other family members are now eligible for additional survivor or dependent benefits.

12. Most people get back more than they put in

Worried that the money taken out of your check to fund Social Security will never come back to you? Over the years, studies have shown that most people receive more in benefits than they paid into the program. The Urban Institute issues reports that estimate how much people are paying into the program and what they are likely to receive in retirement benefits. (The reports can be viewed at urban.org.) As a general matter, married couples are more likely to get back more than they contributed than single people, and both low-income and high-income people may receive more dollars from the program over a lifetime than the amount of money they contributed to it.